Ernie Pyle’s 1944 book “Brave Men” saved my novel.

I never expected the research for “Secret Battles” to be so difficult. Hadn’t thousands of fiction and non-fiction books been written about World War II? Hadn’t the 9th Infantry Division – around which my book is centered – been instrumental in three major invasions during that war?

What I needed for my novel was information about the average soldier’s experience, especially in the medical companies that handled the sick and wounded. What I found when I first started looking was limited information about the 9th’s operations and almost nothing about its medical units.

As I have written elsewhere, “Secret Battles” was inspired by my parents’ story. My late father was a surgical technician in a medical clearing company, but I had no idea what that involved. His letters and journals failed to fill in all the gaps in my knowledge.

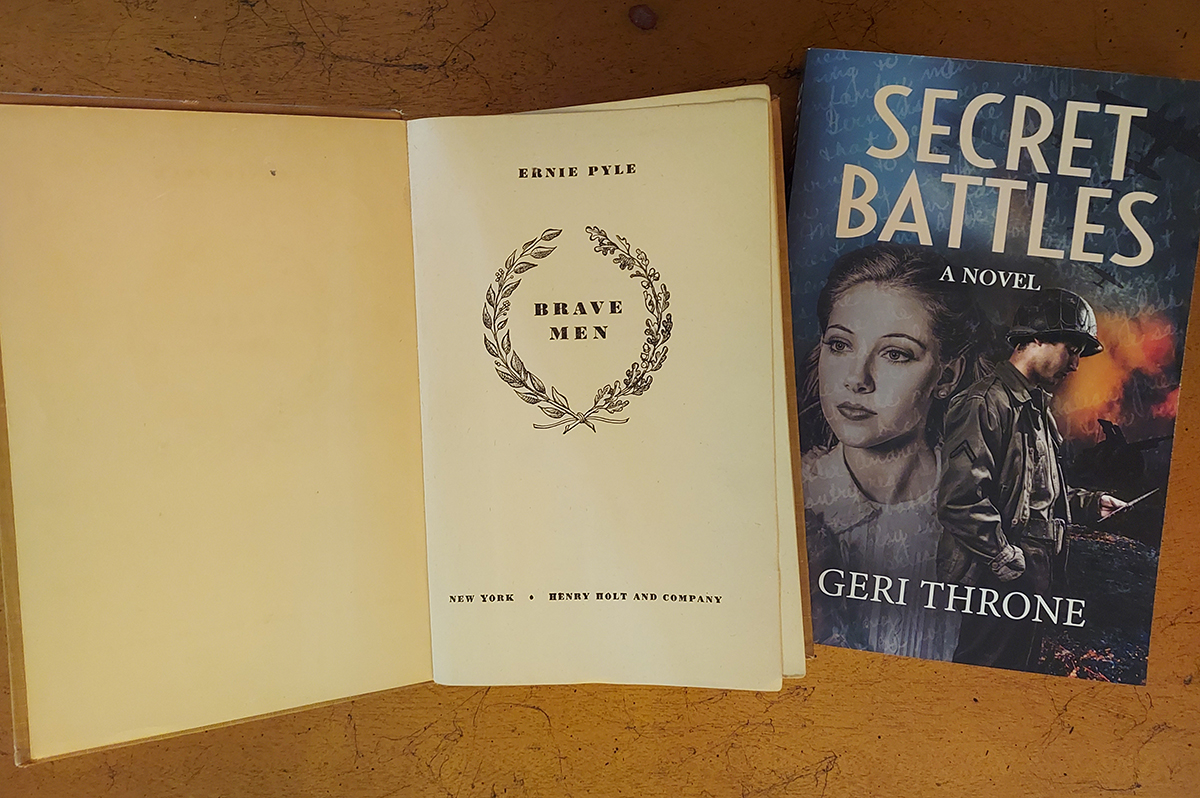

Ironically, my search for information ended in my father’s collection of World War II books. There, I found a worn book with no dust cover: Ernie Pyle’s 1944 book, “Brave Men.” The chapter entitled “Medics and Casualties” included a detailed description of a clearing station in Sicily where Pyle was treated in 1943.

I should have known Pyle would help me out.

The Pulitzer-Prize winning journalist and war correspondent was beloved by troops for his ability to capture the stories of ordinary American soldiers in the war. Tragically, he was killed by enemy fire in 1945 during the Battle of Okinawa.

Pyle didn’t write about the Ninth Infantry in that book, but he did give a detailed description of what he saw when an ambulance took him to the 45th Division’s clearing company after he fell ill. He called the station “a small tent hospital. . . a sort of flag stop for wounded on the way back from the lines.”

At last, I discovered what a soldier went through after he was wounded in combat. The wounded first received immediate, needed aid, Pyle wrote. Then litter bearers took them to an outdoor battalion aid station, which consisted of a battalion surgeon with little shelter, his medical chest, an assistant and a few stretchers. From there, those needing more care were taken to their regiment’s collecting station, run by five doctors and a hundred enlisted men. Wounds might be redressed and more morphine might be given. The goal was to operate as little as possible until a soldier reached a real hospital, but often surgery was necessary at the collecting company.

From that point, soldiers needing more care were taken a few miles back to the division’s clearing station, which Pyle described as a small hospital.

For the first time, I gained a mental image of my father’s surroundings during the war. The 45th’s clearing company, Pyle wrote, had five doctors, one dentist, one chaplain and 60 enlisted men, including medical technicians. They worked in six big, floorless tents and a few small ones. My father’s company likely was twice that size, broken into two platoons.

Pyle described the operating tent in the 45th as having two large army trunks upended on a dirt floor. Inside them were drawers containing surgical supplies. When a wounded man was brought in, his litter was put atop the two trunks. One or two doctors then tended to him, while technicians using steel forceps handed the doctors sterile compresses or bandages.

Pyle was amazed by his company’s efficiency. “The station could knock down, move, and set up again in an incredibly short time. They were as proficient as a circus. Once, during a rapid advice, my station moved three times in one day.”

At that point in the war, actual hospitals were another forty miles or more to the rear of fighting. A gravely wounded man unable to endure that long transport would have been taken immediately to the clearing station’s surgery tent, which is where my father worked.

Surgery at that point was still risky, however. Many doctors in clearing stations had little surgical experience. Not until the last days of fighting in Sicily did the Army improve that situation by stationing mobile field hospitals near the clearing companies.

Pyle answered almost all my questions about the mechanics of a clearing company, but whenever I needed more detail, I called the man I mentioned in my previous blog entry. Herb Stern, who was the company’s clerk, just turned 102. I wish my memory was as keen as his.