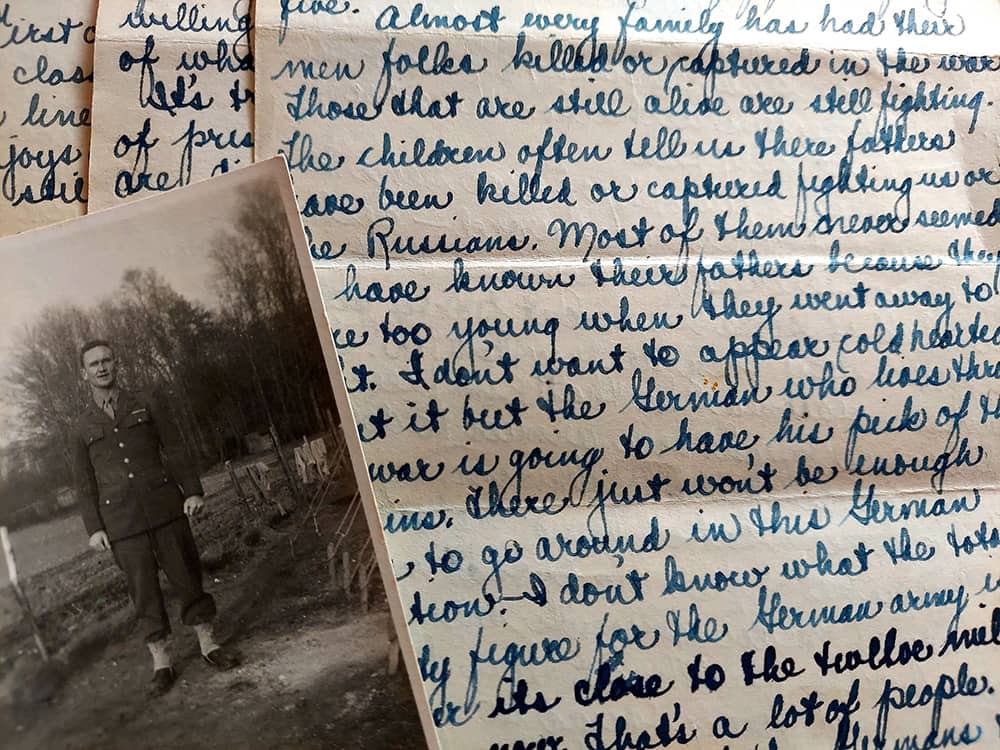

Handwritten letters felt like lifesavers during World War II, a slender thread of connection during an era of danger and loneliness. For the most part, they were written in cursive. Educated people used that writing technique, which was nothing like calligraphy of old. Cursive was more practical than artistic. Students learned it in elementary school.

Except for my father. He failed penmanship in second grade — the only child in the history of his Catholic school to do so. He seemed almost proud when he told us that. I suspected he relished the rebellious effort it took to fail at something so basic.

The nuns must have hated his handwriting. They made him practice the corpulent connected circles and gently slanting spikes of the popular Palmer Penmanship method over and over, to no avail. He had a steady hand and a good eye, but even as a boy he thought Mr. Palmer’s method was an uneconomical waste of writing space.

No matter. I loved my father’s handwriting. It was as unique to him as his wheezing cough, the half growl, half high-pitched whine of his cigarette-scarred lungs.

On Sundays, he would drop us at the church door early to find seats. But by the time he parked his Olds 98 and grabbed one more smoke, the Mass was moving along. He rarely spotted us amid St. Philomena’s crowded pews, but we always knew he was there. The distinct phlegmy whistle of his cough from the back of the church was as reassuring as the jingle of the altar boys’ small, brass bells.

His handwriting was like that, too—a solid sign of him. No one ever reined in the excesses of the Palmer method as efficiently as he did.

To keep the nuns happy, he said, he occasionally forced himself to paint the fat, wide O’s and lazy, uncrossed T’s that they demanded. Most often, though, he resorted to the neat, cramped cursive he preferred all his life. In every way that mattered to Mr. Palmer and Sister Mary Theresa, he violated every rule of elegant handwriting.

His letters of the alphabet stood at rigid attention, shoulder to shoulder. If they leaned too far right or left—or stretched too high—they violated his sense of symmetry. Packed securely and lined up straight, his words took on the strength of tightly laid bricks. Compact and self-assured.

But cursive can fight back when you rein it in so tightly. My father’s desire to squeeze as many words as possible on a page created an odd byproduct. Loopy curlicues adorned his Ts and Fs and Gs and Ks as he made quick, tight turns racing from one letter to the next. As sturdy as his words stood, the overall effect was that of a cramped gingerbread house.

Not until I left home for college at 18—about the same age I couldn’t wait to be free of him—did I begin to find solace in his predictable penmanship.

Like unexpected gifts, his long letters clogged my college mailbox with lively observations and deep thoughts. His sentences overflowed into margins. His words filled each page, front and back. He crammed the pages into envelopes too small for the job, as if seeking a way to send himself.

In person, my father was funny and smart — and picky, sarcastic and demanding. On the written page, he was a dad of 1950s’ television: warm, wise and affectionate. His letters shared worries about his business, delight in a Sunday drive, pride in his vegetable garden, awe in a saffron sunset. His written language felt friendly and familiar.

No wonder the mere sight of his unique handwriting in my mailbox was enough to lift my spirits.

I relived that emotion as I did research for my novel, Secret Battles. My late father seemed to sit by my side as I read his war letters and journals because every entry was written in that defiant style of his. Then I recalled that his wasn’t the only handwriting I once could recognize on sight. Back before long-time friends and I switched to truncated typed text messages, we kept in touch through frequent handwritten letters. So unique were their handwriting styles that the lettering whispered their names to me before I opened their envelopes. Even those who might have earned an A in penmanship in second grade had added their own special twists and turns.

Imagine the joy a soldier in World War II must have felt when he spotted his loved one’s handwriting during mail call. Or the thrill she also felt seeing his script in her mailbox. They heard each other’s voices without a word being spoken.

Thanks for sharing about grandpa. It’s neat to get to know him on a different level from your perspective. I’m really looking forward to reading the book and discussing with you in person. Congratulations to preserving!

Thanks, Jenna! I have so many stories about him, including some events detailed in my novel. But I remind family members that this novel, though inspired by my parents’ stories, is fiction. The husband and wife are fictionalized characters. The parts I tried to keep strictly factual were the challenges faced by the Ninth Infantry Division overseas and by families back home in the United States while the war was going on. My research for the book taught me a lot.

Beautiful, Geri. And personally familiar. I too received poor marks in grade school penmanship, was sentenced to hours of reproducing swoops, swirls and circles (and my handwriting never improved), as well as waiting for and cherishing each handwritten message from home during my time in Vietnam.

Thanks you for sharing that memory!

I think you’re very fortunate to have such wonderful memories of your father; something I wish I had. I love your way of writing and retelling the stories of your life with your father. Congratulations on the book! That’s amazing!!!