Radio took center stage in the 1930s. Sixty percent of American households had one as their main source of news and entertainment.

Thanks to radio, a rabble-rousing Catholic priest grew famous in the ’30s championing anti-war isolationism. At its peak, the broadcasts of Father Charles Coughlin reached ninety million listeners a week, according to The New York Times.

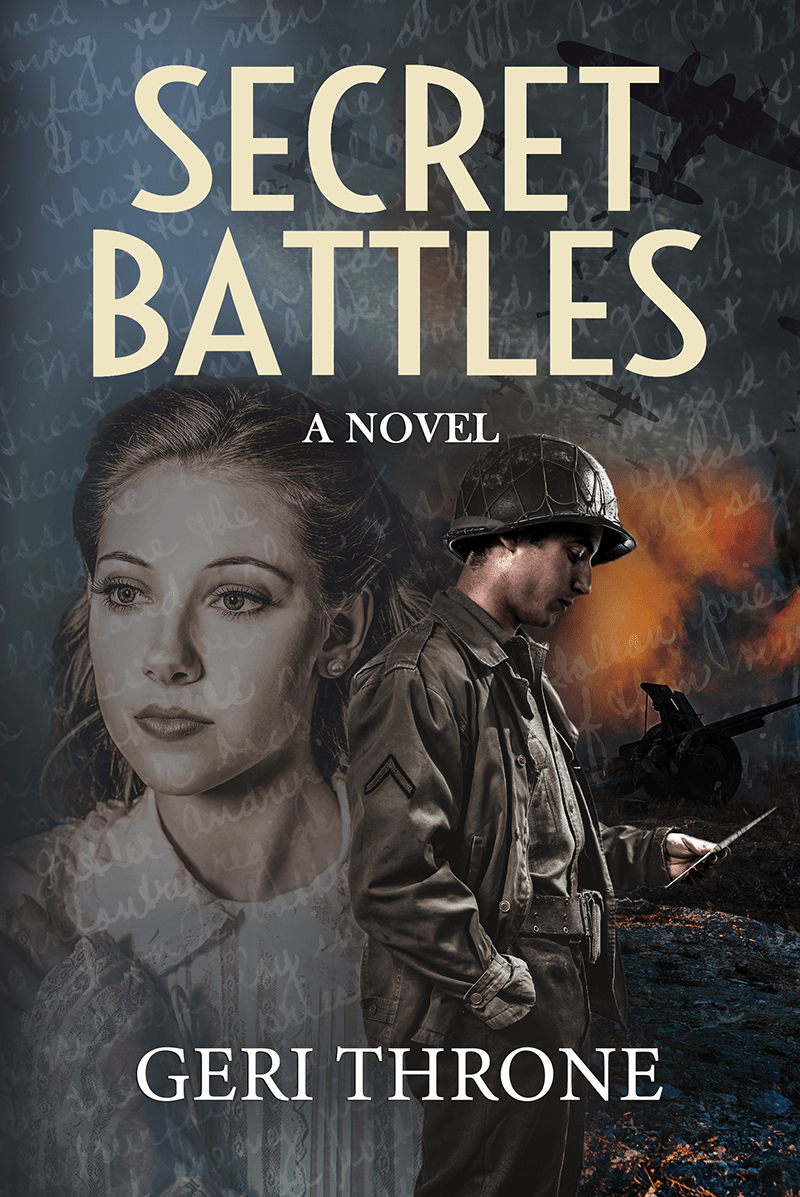

In my father’s pre-war letters, I saw he had listened to Father Coughlin. Even though he was a 1941 Army infantryman, my dad had no interest in going to war. He enlisted in the Army to get his service out of the way, not fight the Nazis. I didn’t expect that. I didn’t know he was an isolationist. I thought few Americans were before World War II. As I did research for my upcoming novel, “Secret Battles,” I wanted to know who this Father Coughlin was. How common were his views?

I discovered that the Canadian-American priest started his radio career modestly in the 1920s as a champion of the working man. He supported Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. But after he split with FDR, Coughlin vehemently opposed the president and any U.S. intervention in the war. By the 1930s, the “radio priest” had become one of the most influential public figures in the United States.

Even more shocking was how the priest grew increasingly anti-Semitic in his broadcasts. In 1938, Coughlin described Kristallnacht, the violent Nazi attack on Jewish communities throughout Germany, as justified retaliation for what he said was Jewish persecution of Christians. He even blamed the Jews for inciting Europe’s strife and praised fascist dictatorships and authoritarian governments. “It would be better to let the Nazis conquer Britain and the Soviet Union,’ the priest argued, “than to enter the war merely for the sake of Europe’s 600,000 Jews.”

Coughlin knew his audience. Hatred of Jews ran deep in the late 1930s. Sixty percent of Americans polled described Jews as greedy and dishonest. Seventy-two percent opposed letting any more Jewish refugees into the country.

Anti-Semitism wasn’t as evident in mainstream political speeches of the time, but anti-war sentiment surely was. In The New York Times archives, I found emotional pleas to stay out of Europe’s war by Republican and conservative Democrat senators, as well as other national leaders. America was deeply divided between interventionists and isolationists.

A leading pressure group against entering the war was the America First Committee, founded by a group of Yale students in September of 1940. The isolationist group included future president Gerald Ford; future Supreme Court justice Potter Stewart; Sargent Shriver, who would later head the Peace Corps, and Kingman Brewster, who would become the US ambassador to Great Britain. Aviator Charles Lindbergh was a prominent spokesman.

About the same time, though, Coughlin was losing access to the radio airwaves due to efforts by the Roosevelt administration. He then relied on a newspaper he published to spread his views. The anti-war fervor he helped stoke remained strong.

In early 1941, for example, Republican Senator Arthur Vandenberg of Michigan made dire predictions about the cost of a long-lasting war. “We are not adequately prepared for such a war,” he said. “We do not want such a war—and every popular poll proves it. Not even the unanticipated defeat of England would justify such a war. It would be the blackest and the most needless calamity in the whole story of American history.”

Vandenberg was right about the polls. By then, Hitler had taken over most of Europe, including France, and had been bombing London for months. Yet Americans saw no need to rush to help. In a 1941 Gallup poll, seventy-five percent favored going to war if there was no other way to defeat the Axis powers. But when asked if the country should enter the conflict at that time, eighty percent said no. The country wasn’t ready.

Tragically, the full truth about Hitler still was not widely known in America. Given the nation’s widespread anti-Semitism, politicians and even Jewish movie makers were reluctant to reveal that Jews were the main target of Nazi persecution. That news, they feared, could backfire against pro-intervention efforts.

Then, on December 7, 1941, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor. The nation’s mood quickly shifted in favor of war. Within days, the America First Committee was disbanded. Coughlin was unmoved. In his newspaper, he denounced the U.S. declaration of war and claimed that Jews had planned the war for their own benefit.

At that point, U.S. authorities began exploring the possibility of indicting Coughlin for sedition. Soon, the priest’s bishop ordered him to cease his political activities.

The “radio priest” returned to being a parish priest in May of 1942. He stayed out of the limelight throughout most of the rest of the war, and until his death in 1979.