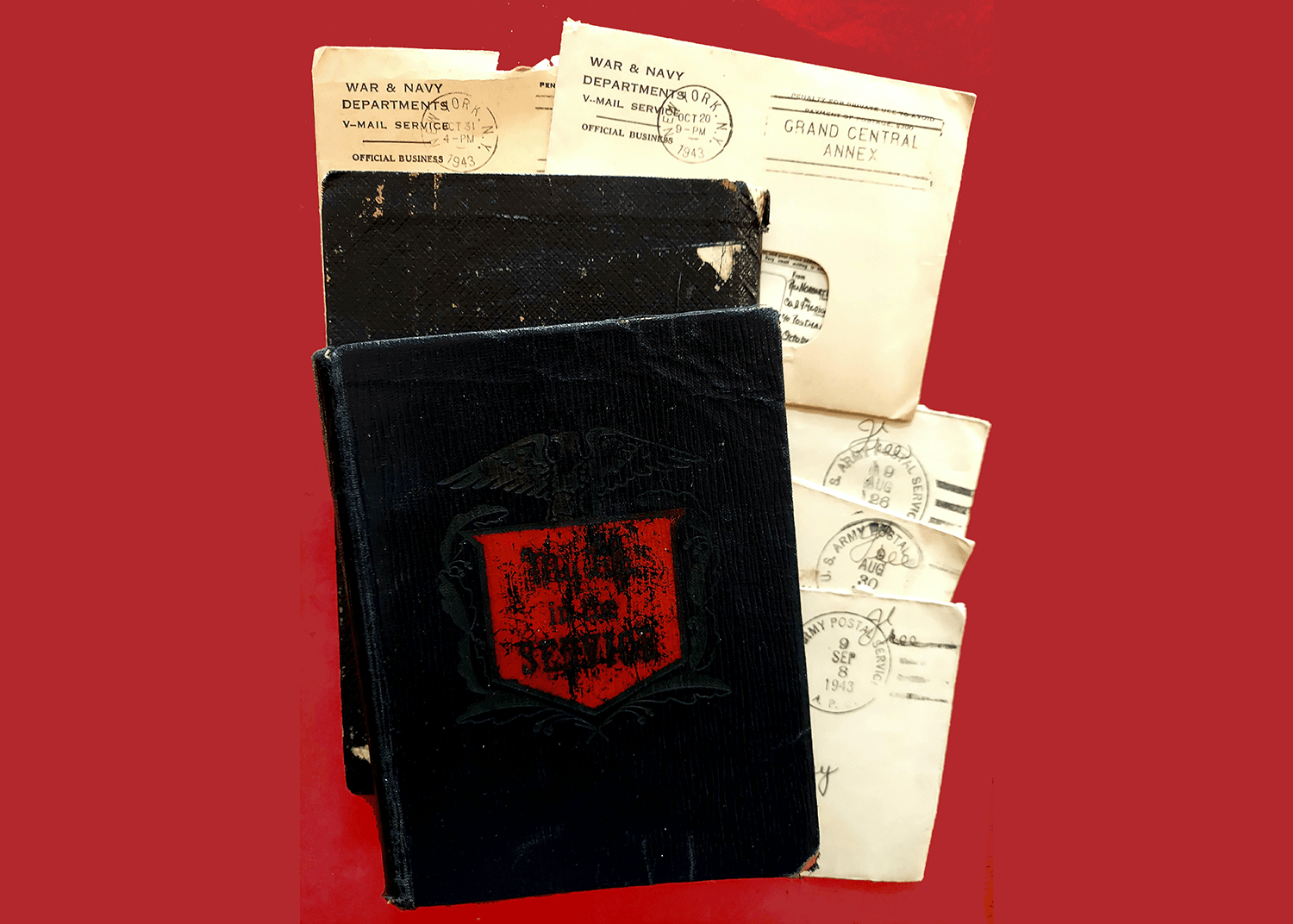

My father was in his 70s when he gave me a cardboard box filled with faded letters and two worn journals. Only after he died a few years later did I read them and discover a mystery: His World War II letters to my mother told one story. His private journals told another.

As far as my mother knew then, my father was safe from harm miles from the front in Africa and Europe. That’s what his letters kept saying.

His journals made it clear that was a lie. Yes, he served behind front lines, but no, he was not always safe. Danger stalked him. Death surrounded him.

What motivated him to keep his secrets, I wondered? Did my mother do the same? Not only were my parents separated by as many as four thousand miles over three years of the war, but their letters took weeks to reach each other. How could a young marriage survive the added burden of dishonesty?

My novel, Secret Battles, evolved from those questions. Though inspired by my parents’ story, the book is historical fiction. I stayed as close as possible to the wartime record of my father’s division, the Ninth Infantry, beginning with the invasion of north Africa in December of 1942 and ending with Germany’s surrender in 1945. But the characters and their personal stories grew from my imagination. I wanted to explore the broader issue of the fragility of truth. War has a harrowing effect on all those it touches—even those miles from the front or a continent away. Absent the truth, how far could love carry them? How far could faith?

World War II censors kept a tight lid on the truth during battle. Troop location, casualties and even hints of poor morale were topics off limits in letters home. The military feared that those and other details would help the enemy if discovered. But as I compared my father’s letters to his journals, I saw that he censored himself, too. His letters glossed over much of what he endured, even topics no longer forbidden to mention.

His journals, on the other hand, held nothing back. Keeping a journal was forbidden, for the same reason letters were censored, but my father, like many soldiers, ignored the order. He wrote about brutal wounds, bombed out cities, constant hunger and trembling hands, about the incompetence of some soldiers and the bravery of others, about near misses and friends slain in battle.

Back home, meanwhile, families devised their own forms of censorship to keep their men overseas from worrying. From my father’s letters, I surmised that my mother wrote glowing accounts of happy family life, rarely mentioning the hardship of scant supplies. She wrote not a word about the difficult birth of their first child.

Soldiers and their families surely had noble intentions when they disguised the reality of their lives. Secrets and lies became honorable tools for survival. But truth is a bridge. It connects us to loved ones. It builds faith. Without constant care, a bridge can collapse.

My Dad was a medic for the Fifth Army. He went through his basic training at Fort Riley Kansas (interesting that my brother and I also went through basic at Fort Riley.) Dad was in the Cavalry and in the early 40s that still meant horses. He finished basic on a horse and then The Army said, ‘oh, we have this new thing called a tank…you need to go back and do basic all over on the new machine…’

He joined the Fifth Army and as a medic he saw General Patton often. He was actually there when Patton slapped that kid and told him to get back out on the front lines.

I don’t think he kept a journal, but I am not sure. I would ask about the war but he did not like to talk about it – so he didn’t. I certainly understood and never pressed it.

Thank you for sharing your story about your Dad. Without good story tellers (writers), us ‘Boomers’ would not be able to glimpse and feel what our parents went through.

Gary,

Thanks for sharing this! I was surprised how often my father commented in his journals about seeing dead cavalry horses along with dead enemy soldiers. There were still vestiges of WWI in that war. I’m grateful to have my father’s letters and journals because, like your dad, mine rarely spoke of his experiences, except to say that if he hadn’t been accepted into the medics, he never would have survived. Every soldier from his original infantry company died in the war.